I keep seeing posts and memes on social media pleading with 2025 to be kinder than its cruel predecessor.

Feels a bit like poking the bear to me. But I don’t believe in resolutions. Manufacturing unrealistic goals leads to certain, but completely unnecessary, failure. I prefer years to be labeled after they’ve ended, like an emperor receiving their honorific, posthumous name.

Last year was my annus dolorous: my year of grief.

It began in January with a sudden, severed relationship. One that I fully expected to only end with literal death, be it mine or theirs. A relationship chiseled into permanence on the thing I hold most precious.

It took me months to accept it wasn’t just a repairable pothole on a rough but passable road. But no, this road hadn’t been abandoned, weeds pushing through the cracks, straining to find a flicker of sunlight breaching the overgrown canopy of trees. This road hadn’t been broken apart with heavy machinery, dirt and debris piled as a barrier keeping you from entering.

This road, my road, had just disappeared as if it never existed at all.

By the end of February, I’d accepted it. It hurt and I hated it, but I went on with life, trying to push back the sadness. Just as I felt like I was processing the loss, I faced another. That was the month I learned half of the land my family had occupied for more than a century was being sold.

Country kids will understand. Those acres might have been farmed for vegetables, grazed by cattle and harvested for timber, but they also served as personal playgrounds, nature’s jungle gyms and makers of memories. There’s not an inch of that property I haven’t played on or explored with my sisters, our sweet blue tick Suzy in tow.

As spring rolled in, so did the surveyors, lawyers and real estate agents. And with them came confusion, fear and anxiety.

Lines were blurred.

Would the house my parents live in still be theirs? Would our kids be able to climb the magnolia tree we’d fallen from countless times? Would the hound dog cemetery, where my first love, a beagle named Duck, and our beloved Suzy—a dog so cherished daddy listed her among his daughters—no longer be ours to visit?

A month later, I watched as the pines my parents had planted to be responsibly harvested and reseeded on a 20-year rotation were removed to make way for the new owner to lay their own foundation.

I cried the first time I came home for a visit and saw it for myself. It was an abrupt ending to a book I hadn’t finished reading yet. What was still ours in my heart was legally theirs; and, somehow more painfully, it was the opening chapter of a stranger’s story.

Grief is a strange thing.

It presents as many emotions: anguish, anger, guilt, resentment, heartache, to name a few. The most dangerous is yearning. From yearning’s deep ache and longing comes nostalgia, the space where genuine and artificial memories blur. Nostalgia can make you think you’re someone you’re not. It gives you a brief, magical break from being a grownup and allows you to feel like a kid again, sitting criss-cross applesauce on the floor, barefoot and dirty from playing all day outside.

My love of reading and learning was born from the full set of Encyclopedia Britannica my grandfather purchased from a door-to-door salesman and put on a shelf for us in that farmhouse. The same one he built with his own hands and a tornado pulled at the seams.

This is the place that fostered my quirks and obsessions. And there were many: dinosaurs (went to archeology camp), space (Pluto IS a planet), natural disasters (Andreas fault’s fault) and conspiracy theories (Lee Harvey Oswald didn’t act alone). You know, normal kid shit.

So when I had to go to Chicago for a week in April, I disassociated from the reality back home. I was suddenly 10-years-old again, ready for an adventure. My hotel was three blocks from the Field Museum, home to Sue, the most complete T-Rex that has ever been discovered.

I was buzzing with excitement when we landed in O’Hare and I skedaddled off that plane toward baggage claim, a decent little walk from the terminal. I started out strong, but halfway there the pain I’d been trying to push away for over a year rolled over me in a sickening wave.

I can’t say what happened, if anything. I think maybe my body just had enough. I managed to get to the hotel and haul all my things to my room. As I sat on the edge of the bed and looked out over Lake Michigan, I knew I wouldn’t be meeting Sue. I’d be lucky to get down stairs to the conference sessions.

For months I’d been going to clinics and specialists, seeking answers to why my body felt like it was being torn apart from the inside. Summer was hard on me, gentle reader. It’s a bigger story for another day. I know I keep saying that, but it truly is. This is as bare bones as I can be.

By June I’d been to a dozen doctors – every kind you can think of: spine, hip, rheumatology, etc. – and for more than 12 months I was repeatedly diagnosed without any x-rays or scans. I was in perfect health, save for one thing. Me and my insurance spent over $100,000 to have all these medical professionals tell me I was FAT.

By my birthday at the beginning of July, I could only move between the bathroom, the bedroom and my home office area. I hadn’t been able to clean or cook for months. The house was a disaster and I was on the verge of a breakdown. Even though I was scared I couldn’t physically function, I decided to go on our annual girl’s trip, three days of rest and decompression we allow ourselves every summer.

A day after my return I lost control of my right leg, along with the sensation of urinating. Mark watched me cry at my desk and begged me to go to the emergency room. There’s nothing wrong with me, I said over and over. The doctors had told me I was fine. Fair enough he said, but maybe at least the ER could give me something for the pain and at least I could get some sleep.

We’d be home by midnight, he said.

On July 7, as Hurricane Beryl churned in the Gulf, a kind ER doctor sat beside me visibly upset. “I’m sorry,” he said. “You have been walking on a hairline fracture of your hip and your back is just…” His words faded.

While they waited for radiology, he’d given me steroids, vicodin and two shots of demerol. The pain persisted and he returned with fentanyl. For the first time in over a year, the pain dulled and I felt hope.

I don’t remember his name. Our encounter was relatively brief, but he did something no one had: he listened, held my hand and promised I wasn’t crazy. Something really was wrong with me, he said. And if anyone had bothered to take one, a simple x-ray could have identified at least some of the damage.

My L3 and L4 joints were bulging and my L5 had completely compressed onto my SI joint, putting pressure on my spinal cord and compressing various nerve bundles, including the sciatic nerve. Official diagnosis, aside from fat, was severe spinal stenosis and a cracked hip.

How did this happen, you’re wondering? I had an accident 7 years ago, but they missed the injuries. I had a concussion and a leg so broken it required two rods and a sack of pins and screws to reconstruct. I was on my back for about 6 weeks and any pain I felt was blamed on that broken leg.

Really, 7 years ago, you ask? Well, remember how I said nostalgia is a dangerous thing? It’s not just memories that become blurred. It also can make you think you’re physically the same person you were 35 years ago.

Specifically, I felt confident I could sled down the beautiful dunes of White Sands National Park just like I did back in ’91. On my first attempt, I experienced what one would call a “rough landing.” It jarred my entire body. My teeth rattled. I immediately regretted climbing onto that saucer sled. Luckily we’d parked at the base of this particular dune so I crawled across the burning sand and used the car to pull myself up.

Mark was wrong. We weren’t home by midnight.

The morning the ER doctor admitted me to the hospital, a hurricane made landfall in Houston. As I watched the storm’s devastation from my bed, others were suffering—but for the first time in 12 months, I felt relief.

Two weeks in the hospital, a rehab facility and phenomenal pain management physician later we were finally making progress.

By October, I was even better enough to go to visit my family in Mississippi. I wasn’t running wind sprints and it exhausted me, but we were able to visit the pumpkin patch and, for the first time in years, I was able to sit and enjoy Mama, Daddy and my sisters. The kids were entertained and husbands occupied. For one magical day, our little, original nuclear family existed again.

When I was able to come home for several days at Christmas, things seemed downright hopeful. I was moving a little better and able to participate in our two days of celebrations. The food, games and gifts were close to perfect. As the kids say: The vibe was right.

My body was healing and so was my heart.

I no longer viewed our new neighbors as usurpers. I watched them come and go from the big living room window. A sweet puppy named Opie bounced in their yard as the young woman smiled and waved at Mama while she checked the mail. They are lovely and kind. Exactly the people you want to have living across the road from you.

The day after Christmas, my niece Grace, the most introverted and serious of the grandkids, pointed to the old magnolia in the front yard and proclaimed loudly and confidently, “I’m going to climb that tree!”

And she did.

Her face beamed down at us as Cody yelled, “I’m next!”

Pretty soon there were three little girls squealing from their perches. They laughed as they reached higher and higher until the branches were too small to scale. As my daughter teetered on a limb like a gymnast on the balance beam, I remembered I was the adult now. It was no longer Cindy and Rikki and me in the tree.

“We are not starting the new year with broken arms!” I yelled. They didn’t hear me. Or if they did, they didn’t care. They were making those same memories. A perfect moment of pure freedom and happiness was being imprinted on their souls.

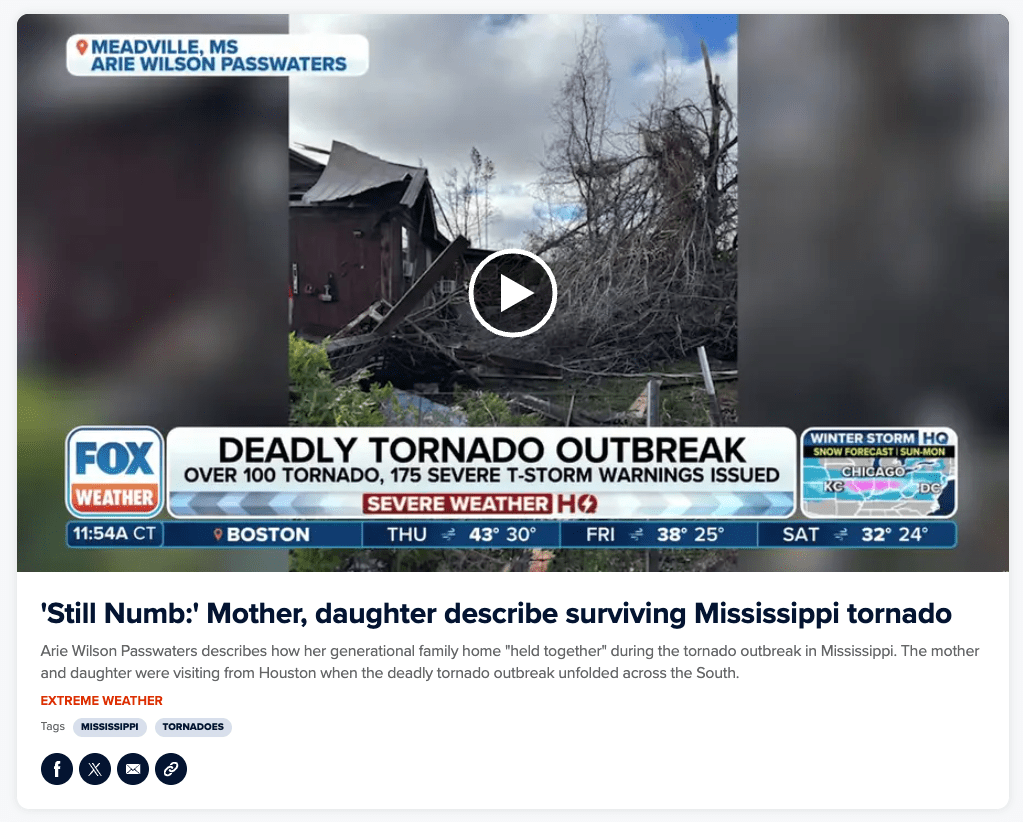

Two days later, stunned and standing on the porch, I didn’t recognize my surroundings. There was sky where sky shouldn’t be. Pines were twisted off as far I could see. The neighbor’s home, the one I’d cried over and came to terms with, was no longer there.

I kept trying to find the magnolia tree.

It’s been 11 days. I’m back in Houston and we are resuming our hectic schedule, but I can’t stop thinking about that tree. And those encyclopedias that I had spent a summer trying to read A to Z. The ancient, outdated volumes had blown away with the northern third of the house, along with most of my high school and college memorabilia.

Last night, as the temps dropped, the cold seeped in my bones and I sought relief in the recliner. Around 3 a.m. I had nearly dosed off with my sweet little pug nestled in my lap. Without warning, the backdoor flew open, hit the wall violently and a strong burst of winter wind washed over me. In my confused, sleepy haze, I thought the tornado was back. I didn’t know what to do. Mama wasn’t here to shut the door.

I must have shrieked, because the next thing I knew, Mark was there, hands on my shoulders.

“It’s okay. It was just Crash,” he said.

Crash, our 125-pound Bernedoodle can unlock and open doors. He’s been known to turn on stove burners and jump out the window whilst cruising down the interstate. He has been hit by a car going 45 miles an hour, and damaged the car.

He’s the happiest, sweetest, most human-like animal I’ve ever met. But his hijinks can be a real nightmare.

And last night, apparently, he was just letting himself into the house after a long day of rolling in sour dirt, stealing a 5-pound container of ground beef off the counter and scaring himself with his own reflection in the window. Why use the custom doggy door specially crafted to accommodate his gigantism, when you can scare the living hell out of the old lady with a busted hip?

Mark bolted the door shut, Crash sauntered off and I cried quietly in the chair and wondered what Volume B would have to say about Bernese Mountain dogs.

Grief is a strange thing.

It rolls over you, manifesting as sadness for the loss of a book you haven’t touched in three decades.

Or guilt as you watch the neighbors you hadn’t wanted lose everything.